Winn Collier, Peterson Center Director

Pilfering through the cabinets at Christ Our King Presbyterian’s library, I found boxes of cassette tapes affixed with old, wrinkled labels chronicling decades of Sundays when Eugene was their pastor. I carried several home; and weeks later, I pulled a bulky Radio Shack player out of storage, slid a yellowing cassette into the slot, and hit play. The spools whined and lurched. The voices were scratchy and muffled. The recorder moaned as if in pain.

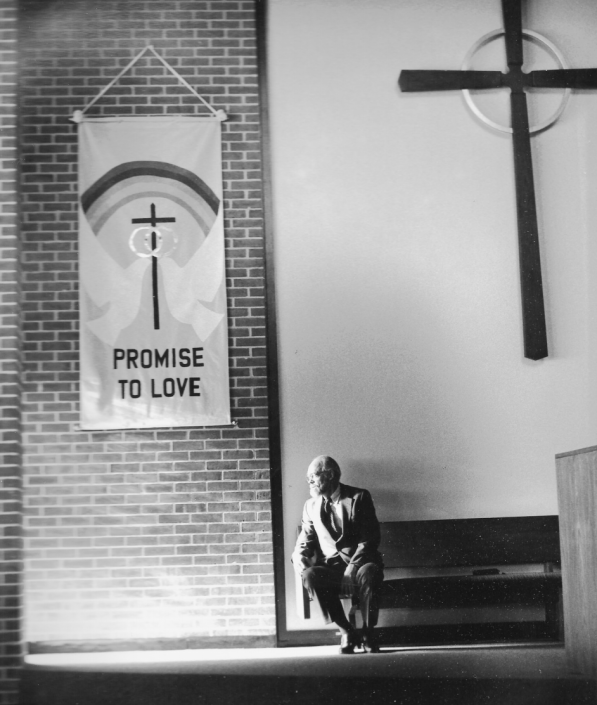

There was an opening choral piece, distorted notes laboring from the black box. After the song, Eugene stepped to the pulpit. He cleared his throat and fumbled with his Bible. I turned up the volume. Eugene took his precious time. Then slowly, deliberately, in his distinctive calm, gravelly voice, he said three words: Let us worship.

Then silence. Awkward silence. But I found myself leaning forward, pulled toward that voice, that space. Pulled toward God. How could these three simple words—via this atrocious, low-tech apparatus and such a plain invitation—how could they usher me into an encounter with The Holy?

Eugene was a masterful writer, but he was not an extraordinary preacher. His journals reveal seasons when he felt his preaching pulsed with vigor and Spirit-life and other seasons when his sermons were anemic and brittle. Once after months of preaching without his notes (he always wrote out his sermons, but his reliance on his pages varied), his wife Jan—unenthused with the results— suggested he return to the manuscripts. While many of Christ Our King’s members shared heartfelt stories of the immense impact of Eugene’s teaching, they never mentioned pulpit charisma. Rather, over and again, people, in a variety of ways, described their slow but palatable awakening to God’s presence. They describe their soul-stirring as they began to recognize God alive in Scripture, in their prayers, in the baptismal waters, in the bread and wine, in their friendships, in their marriages, in their sorrows, in their work.

They described this joyful weight of Divine presence, and they inevitably also described Eugene’s presence. Unhurried. Curious. Immensely human. Long, meandering conversations. Laughter. No hint whatsoever that Eugene was prodding them to achieve something or that his own ego or reputation as a pastor was on the line. For some, it was unsettling to be part of a church with so little programming or to have a pastor who didn’t prescribe to the normal mechanisms for church growth or ensconced strategies for discipleship. But if those folks stayed, they’d eventually notice how all of life (Sundays and weekdays) integrated into a God-radiating story. Life became prayer. And they recognized how much they appreciated the way Eugene honored God’s unique pursuit of each individual person, nothing cookie cutter. People felt safe, seen for who they were rather than for who they might be. People realized, maybe for the first time, that they actually had a pastor.

For Eugene, being a pastor was unflinchingly about God (and he lamented how this most basic truth needed to be reclaimed). The pastor’s essential job—above every other responsibility—was to stand amid this beleaguered, beautiful world and point one direction, say this one word: God. This is why the Christian act of worship was essential. More than our profuse words, we need to hear God speak. More than our presumptions or agendas or spiritual visions, we need God’s way and wisdom. This is why with Eugene there was so much silence, why he was slow to give opinions, why he envisioned a church out of sync with prevailing ideals. Eugene, in the sacred chamber of his soul, was continually moving deeper and further into God’s wide, expansive reality. He was attuned to a different frequency.

This base conviction—that a pastor’s work has to do with God—explains his dogged challenge to dominant North American pastoral models. Eugene was not a bookish curmudgeon or fixed-in-the-past contrarian who reflexively snubbed technology and modernity (Eugene’s reading transgressed into every field and direction, always soaking up fresh ideas—and he possessed a raucous spirit of adventure and playfulness). Rather, Eugene believed that burgeoning pastoral paradigms (pastor as a leadership expert, celebrity, management guru, fundraiser, CEO, therapist, etc.) inevitably moved God to the sidelines. Lots of God-language but very little God. Very little encounter with the Holy.

However, Eugene’s unrelenting attentiveness to God and to the pastoral practice of holy presence didn’t mean he lived in a stifled, cerebral world. Just the opposite. Eugene used the word imagination a lot—and imagination did not mean fancifully envisioning a world one hoped could exist but really didn’t. Rather, imagination embodies the Spirit-infused capacity to see the world as it truly Is: God’s world, a world bursting with redemption and goodness and ultimate wholeness, even if for the moment we’ve committed ourselves to the shadows, delusions, and trivial narratives. To have a spiritual imagination is to have eyes to see God’s world for what it truly is: the ground where God fills the whole earth with his glory. When God fills the world, we discover every conversation and vocation and human endeavor to be a burning bush. Holiness everywhere. God everywhere.

For Eugene, seeing God as the burning center of life meant that Christian faith was not abstract or disembodied but integrated, personal, relational. “Spiritual theology means that everything in the Scripture can be lived,” he said. This is why Eugene’s gardening and carpentry and birdwatching and Shostakovich’s compositions and Levertov’s poetry and Stegner’s novels were intertwined with prayer. Whenever someone asked Eugene how to pray (one of the most important questions a pastor could receive, he believed), he’d ask: “What do you love? Where do you feel most truly yourself?”

This is why Eugene wrote The Message not for the broad, general “Christian market” but for particular people (truck drivers, teachers, defense contractors, farmers) sitting in the pews of Christ Our King. This is why Eugene felt out of place in halls of power (at the White House and around the tables where people wear titles and accomplishments on their sleeves) but was at ease with plainspoken folk and was most comfortable in his denim shirt and boots. This is why Eugene rarely agreed to speak at large conferences where he was on stage under bright lights talking to a sea of faces but to no one he knew by name. This is why Eugene felt uneasy when churches grew too big. After a certain size, he thought it impossible to know people’s names and stories, that the church would lose the relational binding essential to a truly shared life in God. He feared pastors would become managers or institutional spokespersons rather than a pastor.

Every stitch of these pastoral threads—the holiness, the humanness, the redeemed imagination—grew, Eugene insisted, in the soil of ordinary life. In the immediate place that we find ourselves. With the people, God has given us. While pastors may be vexed with the seductive temptation to build a successful religious organization or to absorb and then emulate the corporate-speak of leadership maxims (and Eugene was convinced ambition was the bedeviling sin for many American pastors), Eugene believed that to be a pastor was to be present with the people, to give oneself to the long, tedious and unremarkable work of sustained, physical presence. Sharing wedding vows and grieving at a graveside. The joy (and agony) of children. Careers going south. Bad news from the doctor. Years perhaps when nothing seemed to be happening at all. This work could not be rushed. It could not be charted and measured. It must be lived over a lifetime, trusting that the God of small, dying seeds would once again, by the end of the story, resurrect lush and dazzling life.

Eugene spent his life living his conviction that to be a pastor is to be present with the people—and then with these dear people, to find our common life and future subsumed by the Triune God who fills all in all.